Activist Filmmaking that Keeps People out of Prison

by Charlotte Carpenter

We could conceivably use filmmaking and documentary techniques for something different. Not just educating the public, or inspiring others, or creating art. But for an informative tool to influence the very decision about the rest of someone’s life.

– Rebecca Grace, Founder of Complete Picture

The United States is the world’s leader in incarceration. Currently, there are over two million people locked away in U.S. prisons and jails. Roughly half of this population is imprisoned for low-level drug offenses, property crimes, and various offenses related to their poverty. Nearly half a million people are imprisoned because of their inability to pay for their release. Rigid policies and practices resulting in harsher and longer sentences within our country’s so-called “criminal justice system” (constituted by thousands of federal, state, local, and tribal systems) is the main driver behind the increase in people forced to endure an experience that more often results in trauma and recidivism, rather than rehabilitation. The racial component of this picture is impossible to ignore. A 2022 study by The Sentencing Project found that “Black and Latinx residents are incarcerated at rates five and three times higher than white residents, respectively.” As data around these trends mounts, it is evident that incarceration is simply not a just nor effective means of achieving public safety.

At the atrophied heart of this system are the courts, judges, and hundreds of thousands of convicted individuals whose lives are in limbo as they await their sentencing. Up to 80 percent of criminal defendants cannot afford a lawyer and yet state and county spending on indigent defense has trended downward. On the rise, however, is money spent on parole and probation officers who regulate the lives of some 4.5 million Americans who could be sent to prison at any moment for a minor infraction. The parole-to-prison pipeline is a less-discussed but major feeder of mass incarceration. Many social justice advocates consider the system to be broken and beyond reform, yet many strong-willed individuals have made it their life’s work to attempt to mitigate the systemic harms wrought on society’s most vulnerable by working within its constraints.

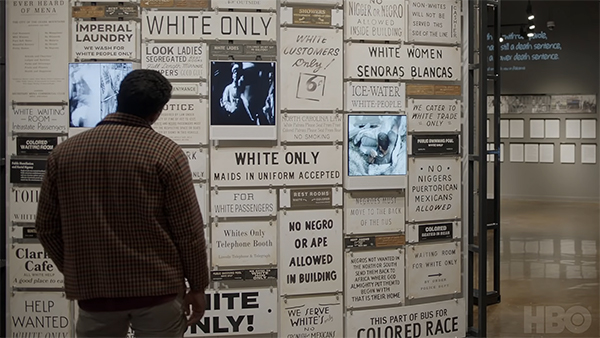

Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative is a prominent example of an individual who champions the cause of challenging the fundamental injustice of America’s criminal justice system as the most important civil rights struggle of our day. The 2019 documentary True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality, which has been adapted into a narrative feature film, provides an inspiring glimpse into Stevenson’s fight to confront the legacy of racism and inequality built into the courts. With no Black lawyers for guidance or mentorship, Stevenson nevertheless decided to pursue a law degree from Harvard in the 80s and soon found his calling as an attorney representing death-row inmates in Alabama – a state with the highest per capita capital sentencing rate in the United States. Through this work, he repeatedly witnessed the ways overwhelmingly white courtrooms unfairly applied the death penalty based on race and class, in essence continuing the legacy of racial domination and terror in the South that began with slavery, continued with lynchings, and transformed into state-sanctioned murder.

In 1989, Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery Alabama as a nonprofit organization “committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, to challenging racial and economic injustice, and to protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society.” Through EJI, Stevenson and his team have successfully represented hundreds of clients who have been wrongfully convicted or unfairly sentenced. Over the years, Stevenson’s steadfast passion has extended beyond the domain of law and into the more ephemeral realm of public memory. As True Justice documents, Stevenson has poured immense effort into catalyzing a narrative shift in the United States that would compel the legal system, government, and the public at large to acknowledge the truth about the history of racial inequality in the country and the ways it continues to affect the life outcomes of people of color. In 2018, EJI opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice to commemorate the nearly 4,000 people who were lynched in the South from 1877 to 1950. That same year, the Legacy Museum was opened in Montgomery, which exhibits materials that narrativize the history of slavery, segregation, and mass incarceration. True Justice ends with this compelling message from Stevenson:

Most people think that if they had been living when mobs were gathering to lynch Black people on the courthouse lawn they would have said something… and the truth of it is, I don’t think you can claim that if today you are watching these systems be created that are throwing away the lives of millions of people, destroying communities, and you’re doing nothing.

It is impossible to encounter the work of someone like Bryan Stevenson and not reflect upon your own actions. Few like to think of ourselves as being complicit in the injustices of the world, but so many feel like the scope of our skills and personal power simply falls short of what is required to make a difference. It is the rare person who possesses the talents of a death-row lawyer or civil rights spokesperson, but I believe that we each have a role to play in advocating for the poor and incarcerated. As a video-journalist and filmmaker, I have long wondered what that role could be for me. I have been inspired by the power of documentary to shed light on the subject of mass incarceration and the individuals struggling within the dehumanizing bounds of the criminal justice system. Gideon’s Army (2013) by Dawn Porter is a particularly poignant film about three public defenders who have committed their lives to the bleak and often thankless work of trying to keep people out of prison. The film highlights the enormous pressure placed on poor defendants to accept guilty pleas because they cannot afford bail, and the limited capacity resource-deprived public defenders have to help them when their caseloads number in the hundreds at any given time.

Another notable film that has enriched my thinking on this subject is Brett Story’s 2016 documentary The Prison in Twelve Landscapes, which takes a more oblique yet no less incisive approach to portraying America in the era of mass incarceration. Through twelve place-specific chapters, Story examines the subtle ways carceral systems have permeated throughout the fabric of American society. She turns her lens on infamous sites of racial unrest like St. Louis and Baltimore to highlight the ways discriminatory local laws keep communities of color oppressed, as well as small hamlets in Appalachia where poor white people express enthusiasm for the new job-generating federal prisons being built in their towns. With few words but many powerful images, the film makes a strong argument that prisons and the logics that undergird them speak volumes about what and who we value, and don’t value, as a country. Just because human cages are out of sight and mind for many of us, does not mean we are not implicated.

As edifying and moving as documentaries like these are, they always leave me with a certain uneasiness and frustration with the limits of filmmaking. Have I tricked myself into thinking I did something simply by virtue of watching them? Is reality on the ground any different because this film was made? This year I began educating myself about the history of Third Cinema, an ethos of filmmaking rooted in “Third World” resistance to Western imperialism, colonialism, and global capitalism. What drew me to this diverse body of work was the notion that film could do more than simply reflect a neo-liberal worldview back to a neo-liberal audience. Though their subjects range as widely as their nationalities, Third Cinema filmmakers seem to share the idea that the camera can and should be used as a weapon against the powerful and a tool of empowerment for the dispossessed. As Teshome Gabriel writes in his essay describing modern-day manifestations of Third Cinema, “Third Cinema continues to serve as guardian and witness for the under-represented and marginalized, for those whom the system has relegated to the fringes of society, the fringes of the frame.”

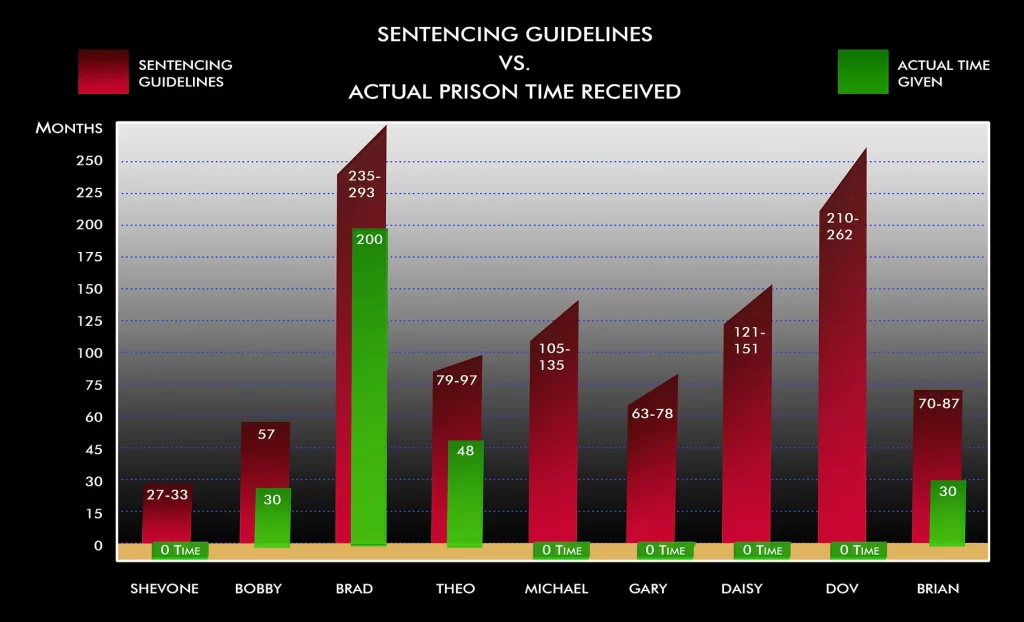

This year I was also fortunate to meet a woman who I believe applies this spirit of Third Cinema to her work with criminal defendants, albeit in an entirely novel and unusual way. Her name is Rebecca Grace, a filmmaker with over 30 years of experience who four years ago decided to dedicate her talents to producing what has become known in the legal world as “sentencing mitigation videos.” A relatively new method of sentencing advocacy, mitigation videos are no-frills 7 to 20 minute compilations of interview segments from individuals who can illustrate a client’s character to a judge in a way that is not delivered through letters or sentencing memorandums. I had never heard of such a thing before meeting Rebecca, but was immediately fascinated by the concept and impressed by her commitment to doing this work exclusively for people who cannot afford legal representation. Her small production company Complete Picture has a 100 percent success rate of helping their clients achieve either reduced time or no time at all.

Over the past year, I have been collaborating with Rebecca to produce a short documentary featuring her work. Ultimately, I am interested in exploring whether video and documentary storytelling has the potential to be an instrumental force in the struggle against mass incarceration. The following is excerpted from an interview I conducted with Rebecca earlier this year. Her words have been edited for succinctness and clarity.

C: How do you view the criminal justice system in the United States?

R: There is so much wrong with the criminal justice system. Money manipulates the truth. People who have money get to tell their story, whether they do it through a high-priced attorney and they can spend hundreds of thousands if not millions to continually fight their case and have witness after witness and report after report and psychological assessments and all of that. My argument is, why can’t indigent clients also get to tell their story?

C: Can you explain what indigent clients are?

R: Indigent clients are people who’ve committed crimes and have to be assigned a public defender because they can’t afford their own representation and that is four out of every five people in the United States.

C: How would you define sentencing videos for those who are unfamiliar?

R: Sentencing videos are a tool to allow those people to tell their true story, the deeper story, of their lives to the judge. We could conceivably use filmmaking and documentary techniques for something different. Not just educating the public, or inspiring others, or creating art. But for an informative tool to influence the very decision about the rest of someone’s life.

C: Do you know how sentencing videos first came about?

R: The invention of sentencing videos was really quite brilliant, and it’s a really great use of filmmakers’ talents who are willing to accept the fact that the audience they’re creating a film for is just one, and that’s that judge. I have to credit the invention of sentencing videos to a few attorneys out there in the world who are so dedicated to their craft and so caring about the people they represent, and they’re just desperately looking for ways to get a fairer sentence. Most defense attorneys lose their cases – case after case after case.

C: What personally motivated you to begin making sentencing videos?

R: There was of course a question, should I help to keep someone out of prison if I can by using the power of filmmaking. And it was a question that my husband and I didn’t grapple with for very long because he had been sent to prison for a drug-related crime because he had been addicted to crack for a decade, and I had been unable to find a way to tell the judge that he was in need of rehab and that he was a very good man and a kind person who had a problem and needed help. There was just no way for me to explain that to the judge. But that’s what really opened my eyes that something needed to be done for regular people to have due process who can’t afford an expensive attorney. They may not be on death-row, their lives might not be at stake this very moment, and they might not actually be innocent, but they still matter.

C: The clients you work with generally have experienced a great deal of hardship in their lives. You seem to be able to relate to them in a way that allows them to open up about their pasts. It makes me think you may have had similar experiences?

R: I was blessed with all kinds of challenges like extreme poverty, complete lack of education, not believing in my own intelligence. So I have some of the experiences that the clients I work with have, and probably just enough that I’m welcomed into their lives. I don’t know what it’s like to navigate in a world where I have to deal with racism, so there are many ways that I don’t relate. But I don’t think it matters too much to the clients I work with because I think they can quickly tell that I have had enough hard knocks myself that I’m not judgmental and that I’m understanding. I get that some small setbacks in your childhood and in your teenage years can really be a deficit to you as an adult and can insidiously eat away at your progress. It takes so many years to overcome trauma. Really most people in our criminal justice system are survivors of some kind of trauma.

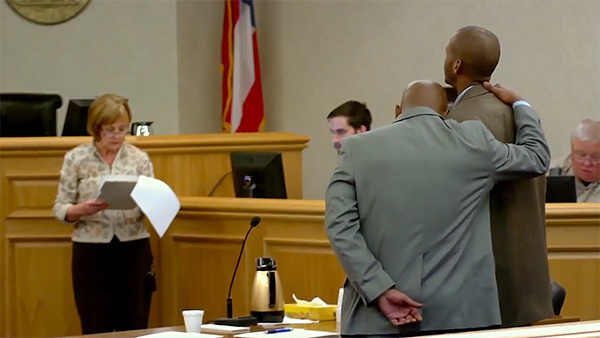

C: How have you seen Complete Picture’s videos make a difference in the courtroom?

R: Every single time the judge has watched one of our videos they have deviated from the probation department’s recommendation. The probation department works for them, they usually trust their probation department’s recommendation and follow that. But when they’ve seen a sentencing video, something inspires them to have a more empathetic response.

C: Can you put your finger on what exactly produces this increase in empathy?

R: I think what is inspiring them is that the facts that have been given to them, they’re able to interpret those facts through a story. When they can see a story described to them through all the members of that person’s family and community, it makes them more willing to embrace another person’s reality.

C: What elements are typically included in a sentencing video and what is left out?

R: There’s not anything extraneous in the video that isn’t important for the judge to understand or see. We don’t use music, it’s not poetic, it’s not overly emotional. We know that the judge needs to understand a person’s level of remorse. We know that the judge needs to understand what the mitigating circumstances are. Is there mental illness or substance use disorder? Does this person have some kind of disability that is misunderstood? What are alternatives to incarceration that could really work? In a sentencing video we’re touching on all of these factors.

C: This work keeps you extremely busy. How do you see Complete Picture growing in the future?

R: One of the things that attorneys and judges and people who provide grants to Complete Picture are always complaining about is,”is the scaleable? How can you do this cheaper, how can you do this faster?” And I’m like, “nuh-uh, I’m not doing it.” I’m holding the line. That’s the problem with the system already. Why would I want to replicate that?

C: Why do you think someone who may not fear being sent to prison because of the race or class privilege they enjoy should care about mass incarceration? It’s easy to not pay attention to something if you don’t think it affects you.

R: One in every three people of working age in the United States has a criminal record. It’s not that far-fetched to think that you may accidentally commit some kind of a non-violent crime. Most of us have committed some kind of crime, maybe no one ever found out about it, that might have landed us in prison. And because our system is rigid and uncompromising, I don’t think any of us should feel safe… It costs taxpayers about 81 billion dollars a year to incarcerate individuals all over the United States, but there’s so much more than that fiscal cost. There’s a human cost when a person leaves their children behind and their children are sent to foster care, when they’re no longer able to care for their elderly parent, when they can’t continue to help their partner pay the mortgage or finish college. It’s hard for me to see anyone go to prison. I don’t think it’s right, regardless of the crime or how heinous it is, to inflict torture on a person. I think that’s what it’s come to and it tears apart our society.

So as we all consider what we can do with the skills we have in the face of an issue that has a specific history and scale in the United States but truly reaches around the world, I would encourage us to pay more attention to the “fringes of the frame” and take our cue from those who have been broken by cruel and inhumane systems. In the words of Bryan Stevenson, “It’s the broken among us that can teach us the way compassion is supposed to work. It’s the broken that can teach us the way mercy is supposed to work. It’s the broken that can show us the power of redemption and justice.” And may we all have the courage to confront our own brokenness (for no one leads a wholly human life under capitalism) and do our part to put the pieces back together, better.

RESOURCES

For getting educated on prisons, policing and the courts:

https://theintercept.com/justice/

https://www.themarshallproject.org/

https://www.sentencingproject.org/

https://criticalresistance.org/resources

https://www.8toabolition.com/resources

Media organizations that distribute work on mass incarceration/policing:

https://www.pbs.org/pov/film-archive/

https://www.wmm.com/catalog/subjects/law/

https://www.hbo.com/movies/genre/documentary

Festivals:

https://www.injusticeforallff.com/ (Chicago)

https://justiceontrialfilmfestival.net/ (Los Angeles)

https://mmjccm.org/arts-film/film/cinematters (New York)

https://socialjusticenowfilmfestival.org/ (Los Angeles)

https://www.allrisefilmfest.org/ (Cleveland)